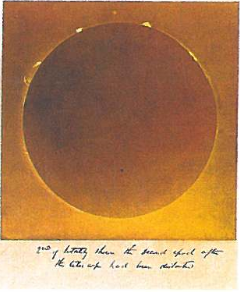

SiO2 two ways – 2016

Photographs with gravitas

Can you call to mind any photographs you’ve seen recently that you think stand out from the rest? That are worthy of retaining in your precious and limited mind-space? That have a place in the story of your life, your family, or your community? Perhaps even in our global human story?

Unlike the others whose provenance and prospects are of no more than momentary interest, these few note-worthy images arouse more than a momentary pique of curiosity, and somehow inherently seem to matter. What they represent is important. How they came to be is important. Who created them is important. How they can be used is important. Somehow, they just seem to have gravitas.

For these sterling images, we widen our field of vision and consider more than just the meaning and aesthetics being communicated by the image. Depending on our experience and perspective we might consider some or all of many things: provenance, photographer, context, resolution, identity of subjects, and more. What constitutes ‘an important photograph’ is not the same for everyone.

An environmentalist might want to preserve an image because it appears to capture a rare event of black swans flocking in enormous numbers on the New South Wales south coast but she might wonder if the swan numbers were artificially inflated by image cloning (they weren’t).

60 Black Swans – Coila Lake, New South Wales Australia – 2015

Parents might love a particular photo of their children and want to know where the photo was taken.

What *he* said – Harry and Obi Ward – Nisi’s, Cootamundra, 2012

Conservators might be especially interested in the date of the photograph.

Christchurch Cathedral entrance prior to the 2011 earthquake – Sept 2009

In all of these cases, the person standing behind the photograph, the photographer, is indispensable. She or he is needed to tell the story of the photograph – what it depicts, when it was taken, what has been done to it. The credibility of the photographer reflects on the credibility of the photo.

Our photographic reputation

So what about when we are the photographer? As a photographer, we are not judging photographs, we are judged by our photographs. We stand behind them. We have a role to play in acting as a witness not just to the event we photographed, but to the meaning and context of the photograph itself.

Just like any witness, we may be able to rest on our solid reputation such that even unusual photographs will be believed because we are believed. Or we may be unable to convince anyone that we haven’t manipulated an image because we have a reputation for producing images that are more art than true representations of the world around us. Like any other walk of life, our reputation precedes us.

Living in the digital age has both opportunities and challenges. As photographers, the best of our work can be preserved for as long as there is interest in what we accomplished. Unfortunately, so can the worst of our work. From simple sins of omission that leave our photos orphaned because they cannot be understood without context, through to sins of commission like deliberately misleading photo editing, or acts of inappropriate image publication, our worst photographic choices will forever cast a shadow over our best.

And our work can last for a very, very long time. For example, my post “Keep ’em Flying” about a photo of 9 WWII era matchbooks illustrating the early days of pilot training is a perennial favourite despite the events of the story and the matchbook covers being over 70 years old.

Detail of 1940s matchbook cover

By the same token, Henry Peach Robinson’s “Fading Away,” has lingered for over 150 years, and, while a poignant illustration of human frailty, is also a image with no representational truth, being created with staged actors and 5 different negatives. It is photographic art, but not a photograph. It is difficult to know which, if any, of Robinson’s ‘photographs’ are real, and which are fabrications. In the 1860s photography was relatively poorly understood, so it may not be that Robinson’s reputation preceded him, but it certainly succeeded him.

Henry Peach Robinson’s Fading Away, 1860

No one is perfect, but I believe it behooves us to act as honourably as possible in our photographic practices, not just because it is the right thing to do, which should be enough, but in enlightened self-interest. If we care enough to take photographs, we probably care enough to want them to endure. The photographical canon of the future is likely to be an amalgam of the many useful photographs taken by photographers with integrity and character, and the relatively fewer infamous ‘doctored’ photographs that serve as a warning of what not to do. Everything in between, the dubious, the unknown, the incomprehensible, the orphaned photographs may well just be visual noise, given short shrift by our descendants.

The great difficulty is first to win a reputation; the next to keep it while you live; and the next to preserve it after you die, when affection and interest are over, and nothing but sterling excellence can preserve your name. Never suffer youth to be an excuse for inadequacy, nor age and fame to be an excuse for indolence.

– Benjamin Haydon (1786-1846)

Photographs

———–

60 Black Swans, What *he* said, and Christchurch Cathedral entrance prior to the 2011 earthquake, photos by Sabrina Caldwell, other than resizing for web use, no alterations have been made

Detail of 1940s matchbook cover, photo by Brian Bleecker, image cropped and resized for web use by Sabrina Caldwell

Fading Away by Henry Peach Robinson, public domain

SiO2 two ways, photos by Sabrina Caldwell, image was cropped and resized for web use